Coastal Coursework

Pirate undergrads spend a semester at the coast

Under a new program, students can spend a semester learning and conducting research at the Coastal Studies Institute in Wanchese.

As the water warms in the early spring, baitfish school by the thousands and even millions off the coast of North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Gannets and cormorants divebomb the schools from above while bluefish and mackerel attack from below, a roiling mass of life and death just off the sandy beach.

Later, sea turtles venture out of the ocean and trek up the beach to lay their eggs in holes dug in the sand. The fish, seabirds and turtles are all part of the unique ecosystem of our coast — a dynamic, shifting line of sand dividing the unrelenting ocean from the salt marshes and estuaries behind.

Student Marco Agostini works with Kimberly Rogers, an assistant professor of coastal studies, while using the “clementine,” a device that measures sea water conductivity, temperature and depth.

Researchers and students from East Carolina University are drawn to the same delicately balanced coastal environments to study how they work, how they change, how to preserve them and how to harness the immense energy of the ocean’s waves, tides and currents. This spring, four students became the first ECU undergraduates to spend an entire semester at the university’s Outer Banks Campus in Wanchese, taking courses that include environmental anthropology, remote sensing of the environment, and analysis techniques and methods of coastal ocean research.

The Semester Experience at the Coast is open to all majors, and the course credits count toward a minor in coastal and marine interdisciplinary studies. Kimberly Rogers, assistant professor of coastal studies, says each student brings a unique perspective to the table, learning about coastal science through the lens of their own experiences and fields of study.

Marco Agostini, a sophomore majoring in computer science and an EC Scholar, says he learned about the program during an Honors College field trip to the Outer Banks Campus his freshman year.

“So for a year I hounded them and bothered them and said, ‘Hey, is this program ready yet? Are we doing it? What’s happening?’” he says.

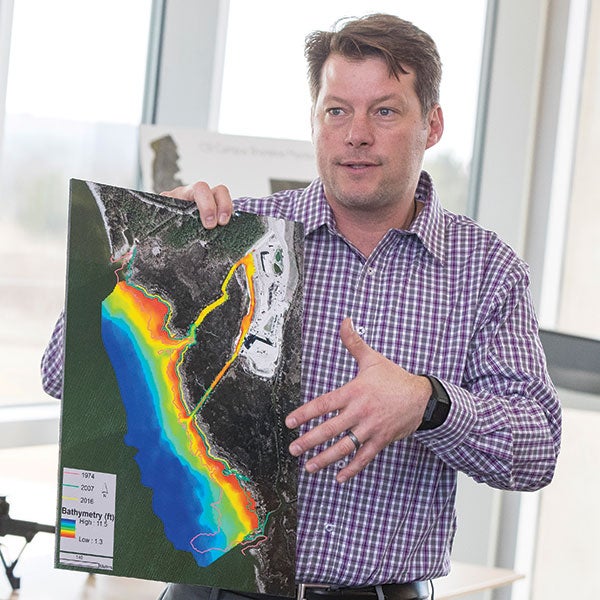

Reide Corbett, executive director at the Coastal Studies Institute, holds a satellite image showing erosion nearby.

The idea was appealing because Agostini wants to find a career that combines his passion for computer science with his love of the environment. He has already started looking at positions and programs related to data science and data analytics at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. The opportunity to spend a semester at the coast and do fieldwork was too perfect to pass up.

“Being able to experience these things in person — we learn about it in class, then we come out here, we see the beach, we see the water, and we experience the things that we’ve learned — it really drives it home,” he says.

On a windy day in February, the students visited Jennette’s Pier in Nags Head to measure the profile of the beach using several methods, the first of which was decidedly old school. Using two stakes and a 2-meter length of string, the students recorded elevations from the dune line to the water’s edge. It was an involved and time-consuming process, taking all four students nearly an hour to record one transect of the beach — about 18 individual observations — and it left plenty of room for human error, Agostini says.

Then they performed the same task using a real-time kinematic GPS, a device that uses the positioning of multiple satellites and a land-based station to record the elevation at an exact set of coordinates with a margin of error of less than 2 centimeters, allowing them to record the data more quickly and more accurately.

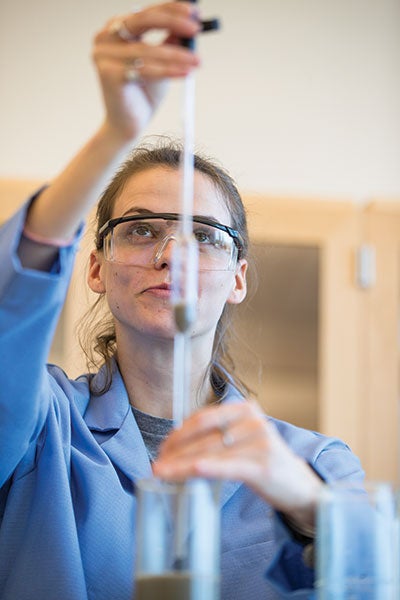

Elizabeth Mason works with sand samples studying grain size at the Coastal Studies Institute.

Finally, David Lagomasino, assistant professor of coastal studies, showed the students a model of the same area of the beach created using a terrestrial laser scanner, which scans the entire beach in a matter of seconds using laser pulses reflected back to the device’s sensors. The data was used to create a 3-D computer model so detailed it showed tire tracks and footprints on the beach.

Faculty member David Lagomasino explains the beach model made from the terrestrial laser scanner data.

“Really I have taken the beach home with me and put it on the computer.”

The TLS provides a high level of resolution, allowing researchers to track minute changes in the beach, but that amount of data means increased storage needs and longer processing time.

“So we have to look at what questions we want to answer and what data we need to answer those questions,” Lagomasino says.

The students also dove into the topic of ocean energy, taking measurements of conductivity, temperature and depth of the water from the pier and using that information to determine whether the Hatteras front — a boundary between cooler and warmer waters that normally converge near Cape Hatteras — had moved north as far as Nags Head.

Rogers says the course offerings are complementary and coastal-focused, but each offers a different perspective.

“They’re getting a 360-degree viewpoint of some of these really fundamental concepts that are shaping the Earth’s beaches, bays and coastlines. And of course, some of the oceanography that is leading to the phenomena that we’re seeing on our beaches,” she says. “They’re going to be much more critical thinkers, and having the experience of being on the water here and seeing these processes, it takes that abstract lecture that they’re getting in the classroom, and they’re seeing it in action.”

Students participating in the Semester Experience at the Coast live in Manteo, about 4 miles from the Outer Banks Campus facility, and the housing and tuition costs are similar to a semester on ECU’s Main Campus. Logan Willis, a senior history major, says the group got along well living together and grew close quickly. They had a standing movie night on Wednesdays at the Pioneer Theatre, which has been operated by the same family for more than 100 years, and planned to go surfing and share other outdoor activities as the weather warmed.

“I cannot imagine spending my last semester at ECU any other way,” she says.

Anthropology major Lauren Wright, a sophomore, says she’s interested in the human relationship with the environment and is exploring a possible career in underwater archaeology. She likes the active, real-time application of research techniques and data collection offered by the program.

Kimberly Rogers watches as students collect data along the beach to the waterline to produce a 2-D beach profile.

“In a standard classroom setting, we’re often just given the textbooks and … here’s the data that’s already been collected. And here’s how it’s already been interpreted,” she says. “Here we are actually taking the measurements, taking in the data and analyzing it for ourselves. I think it’s absolutely amazing.”

As the group wrapped up its observations on the pier, a front moved in, bringing rain and postponing a potential visit to another beachfront location, but with plenty of time left in the semester, their field trip plans still included kayak outings, a pontoon boat trip and wetland visits.

Despite the successful start to the program, due to COVID-19 students did not return after spring break and continued their coursework through virtual methods to complete the spring semester.

Reide Corbett, executive director of the Coastal Studies Institute, said plans are to resume the program next spring and eventually expand it to fall and spring semesters.

ECU’s Outer Banks Campus is home to the CSI, a partnership among ECU and other UNC System schools. Completed in 2012, the facility spans 213 acres of marshes, scrub wetlands, forested wetlands and sound ecosystem. It houses dive and research vessels, a wave tank, and laboratory and classroom space. Major research areas include renewable ocean energy, coastal sustainability and maritime archaeology.