Two Decades Strong

After 20 years, the statewide impact of ECU's public health program is evident

In the fall of 2003, a large class of incoming medical students was joined for the first time by a smaller group of advanced degree candidates studying human health through a wider lens.

This was the inaugural class for the master’s in public health degree who, like their allopathic mates, chose a program, a school and a place — East Carolina University — with a unique focus on rural health care. One was Christa Radford, a graduate with a degree in environmental health.

“At the time, the closest MPH (program) was in Chapel Hill, and public health in rural communities is very different than in the Triangle,” says Radford, an industrial hygiene consultant with state government. “We have to be more creative. Some of our counties don’t have hospitals. The public health department may be looked upon as the health care provider.”

Public health is the science of protecting and improving the health of people and their communities, according to the Centers for Disease Control Foundation. This work is achieved by promoting healthy lifestyles, studying disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing and responding to infectious diseases.

A community health administration track was available through ECU’s Master of Public Administration degree program, but ECU leaders saw North Carolina needed more. “The MPA degree was acceptable,” says professor emeritus Christopher Mansfield, “but it was clear that more academic training in public health was required.”

Mansfield wrote the book on rural health disparities in the region, the Eastern North Carolina Health Care Atlas. It was an educational resource as well as the opening for the master’s in public health. “Health data in eastern North Carolina were among the worst in the nation,” Mansfield says. “Premature mortality was worse than in any of the 50 states. Meaningful improvement would require a transformation that emphasized health promotion and prevention and strategic partnerships between medical and population health experts.”

“There were compelling health disparities in our geographical area,” says Doyle “Skip” Cummings, a pharmacist, Berbecker Distinguished Professor of Rural Medicine and co-director of the E-CARE Practice-based Research Network. “They existed and still exist. (And) there was evidence that not many public health directors in our region had a graduate degree in public health.”

In 1999, the university granted approval to plan the program. Staffing, curriculum, facilities and student admissions took years before a class could muster. The MPH program became a division of the Department of Family Medicine inside the Brody School of Medicine. Financial resources came from several internal and external offices but principally the University of North Carolina System Division of Academic Affairs.

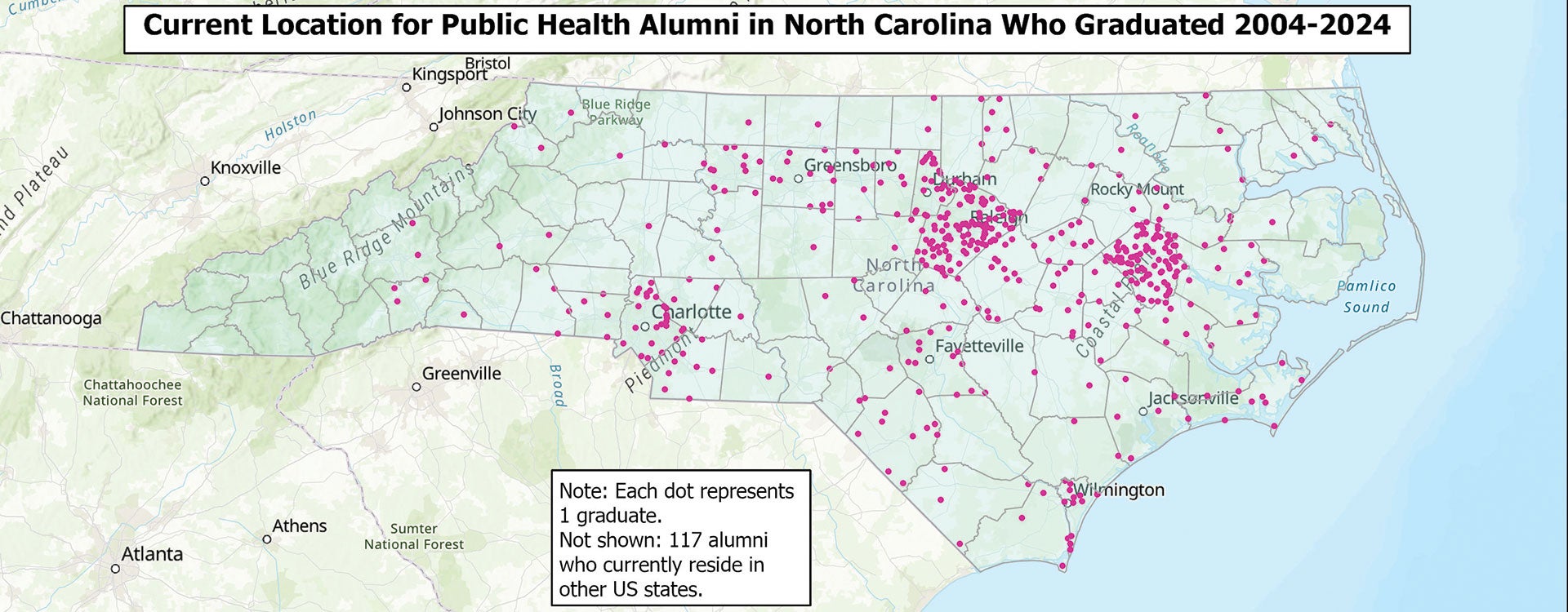

Today, 20 years after the very first ECU Master of Public Health degree holders walked at a commencement, there are about 600 alumni from 76 of the state’s 100 counties, plus some from other states and 12 international students and graduates. Many are employed at local, state and federal public health agencies. Two alumni and one faculty member have served as president of the North Carolina Public Health Association. Faculty and graduates have created a strong and capable workforce in eastern North Carolina that, together with local communities, build collaborations in health needs assessments, better preparedness, more consistent community engagement and a discernable shift toward improved population health — especially, but not exclusively, in the East.

“The program here really prepares degree holders for work in rural communities,” Radford says.

Evidence-based projects

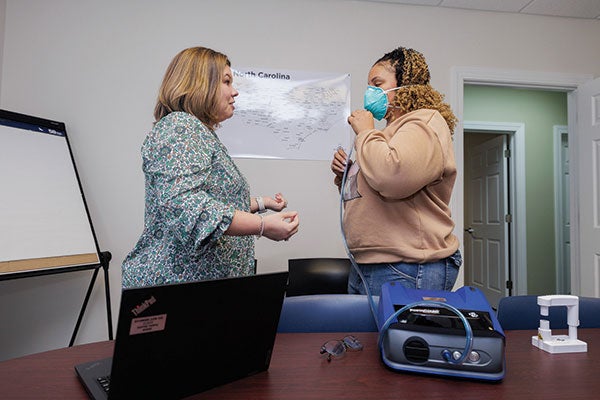

Christa Radford conducts an N95 mask fit test with Tawanna Kirkland, a regional administrative specialist with the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services, using a TSI PortaCount machine. (Photo by Steven Mantilla)

As Mansfield, Cummings and others had hoped, the establishment of the MPH program led to the creation of the Department of Public Health inside the medical school, which has forged research partnerships that have advanced the science of population health.

Consider a set of publications that sprang from a partnership spanning more than a decade with the Albemarle Regional Health Services evaluating farmers market initiatives in northeastern North Carolina. Professor Stephanie Bell Jilcott Pitts directs the research. In 2022, one of her former students, Mary Jane Lyonnais ’17, was lead author of an article about the agency’s prescription produce program in the journal Nutrients.

“We did have some doctors literally prescribe fruits and vegetables,” says Lyonnais, a regional planner at the Upper Coastal Plain Council of Governments. “It was important to us that we were not just implementing healthy eating programs at Albemarle Regional but that we were evaluating them — the data helped tailor the program to rural northeastern North Carolina.”

Through her graduate assistantship with Pitts, Lyonnais became committed to research projects as part of a professional life, not strictly to advance an education.

“The program emphasizes research, and that the community we’re serving should drive the research. So, I’ve been a big proponent of community-based participatory research — making sure communities have access and title to the research and benefit from it.”

The department has led regional health needs assessments, created health councils and led workplace-based health interventions. It has advanced investigations into environmental health (such as exposure to “forever chemicals”), nutritional assessment, chronic disease management, school-based telehealth for mental health and evidence-based interventions for childhood obesity.

Over the last 10 years, publications from research originating in the department exceeded 100, with grant awards during the last five years totaling more than $12.6 million.

Improving health and outcomes

Map by K. Jones, ECU Center for Health Disparities.

Seven years ago, the department added two doctoral programs, one in health policy administration and leadership, the other in environmental and occupational health, which brought aboard four full-time faculty members. Then, two years ago, it added biostatistics from the College of Allied Health Sciences — and five more faculty joined the department for a total of 21.

Graduates support and lead organizations across a range of industries — long-term care centers, industrial hygiene consultancies, food systems planning offices, health departments, water departments, universities and more.

“The health policy administration and leadership concentration of the MPH program has a special track for preparing graduates to be licensed nursing home administrators,” says Suzanne Lazorick, chair of the Department of Public Health. “And there is a designated scholarship program for this track” — the J. Craig Souza Long Term Care Scholarship — “that meets a huge need for qualified professionals in eastern North Carolina — and Truman (Vereen ’15) has become a national leader in the field.”

Another early graduate, Krissy Richmond-Hoover ’06, began her public health career in hospital epidemiology and has gone on to become the health director in Onslow County, serving nearly one-quarter million residents.

Relatively few of them have visited Richmond-Hoover’s public health department, she says, “but that doesn’t mean we haven’t touched their lives.”

Other graduates agree. “When public health professionals are doing a great job, you don’t see it — we make outbreaks not happen,” says Leah Mayo ’13, past president of the North Carolina Public Health Association and assistant dean for community engagement and health equity at the University of North Carolina Wilmington.

In 2018, Hoover returned to the Brody School, this time in pursuit of a doctorate in public health.

“Talking with students in the MPH program now, the strength I see is the commitment to partnering to achieve big (population health) outcomes,” Richmond-Hoover says. “You take a group of like-minded, committed folks, it’s amazing the work we can do.”

“We’re an asset-based mindset, not a deficit-based mindset,” says Mayo, and that means interprofessional cooperation. “I’ve worked with so many people — the police department, the fire department, the local Food Lion — and I’ve never had anyone say, ‘No, I’m not interested in seeing my community improve.’”

Closing health disparities

From the Brody School of Medicine, the Department of Public Health has added synergy and a wide lens to the school’s mission. Vereen, a certified long-term care administrator, says the unique value of training in public health in the medical school is that it’s focused not on career tracks but on a mission: to raise health and wellness in a large, rural, underserved area of the country.

“The program had produced alumni who were directly affecting the health outcomes of eastern North Carolinians,” Vereen learned before he ever applied. “I wanted to be a part of that. I wanted my own legacy within that.”

Still, Lazorick says, “sometimes I have been asked, ‘After 20 years, what has the program accomplished?’”

“We’ve conducted nationally significant research investigations into population health and interventions. We’ve placed dozens of our graduates in leadership in public health agencies and offices. And we’ve continually collaborated with our medical students to give the next generation of primary care physicians a deeper understanding of the persistent challenges to health in rural communities,” Lazorick says.

“I’m not discouraged by the question. I’m encouraged that we continue to focus our research and education here directly at the people who matter most: our eastern North Carolina neighbors and community. At ECU, we strive for regional transformation. The MPH graduates do their part by reducing risks for chronic disease across multiple health determinants and improving health outcomes for North Carolina.”

Recent Accomplishments

- In 2022, the department joined the Association of Schools and Programs in Public Health, the central organization of academic public health in the U.S., connecting ECU to national networking and resources for academic public health. Membership offers access to a centralized application system, which has broadened the applicant pool and enhanced program visibility.

- During the past two years, faculty members have undertaken a complete curriculum revision for the master’s degree based on the most recent accreditation criteria. The new curriculum will take effect this school year, the first major changes in 20 years.