AI has come to campus

And nobody’s panicking. Instead, they’re putting it to work.

Senior Audrey Milks uses artificial intelligence to complement her projects at the East Carolina University School of Art and Design. She described AI as inescapable within the design community.

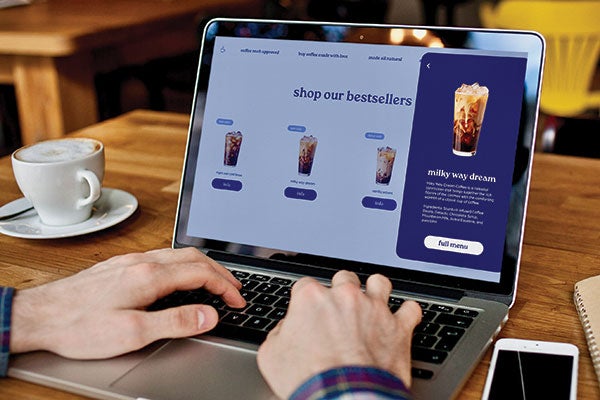

Art student Audrey Milks integrated AI into a coffee shop website design as part of a class assignment.

One example is how she blended AI results with her own creativity for a class assignment to make a website mockup for a coffee shop owner. Milks did all the design work and then asked ChatGPT to create the coffee names with descriptions and listed ingredients. The AI-generated javas were named night owl cold brew, milky way dream and vanilla waves.

This is a process she never would have envisioned when she began at ECU. “I definitely have seen AI evolve throughout my years at ECU,” says Milks, who is studying graphic design. “My freshman year, I barely heard talking or worries about AI within the art department. Now, our professors have AI included within their syllabus and rules. We talk a lot about how AI could be used within our projects.”

Balancing AI results with human intuition continues to evolve. A learn-as-you-go undertone remains in higher education as faculty members try to guard against students overusing or exclusively using AI as their work, if not permitted.

Beyond ChatGPT, various AI tools have permeated everyday life, including in scheduling, patient care, shopping, social media, navigation and facial recognition.

As AI, which relies on machine-learning algorithms and generative models, has improved and become more accessible, university leaders try to ensure increasingly popular AI tools are used responsibly in the classroom.

“AI in higher education is a journey of discovery — one where students and educators are learning as they go, adapting to new tools and techniques that reshape the classroom and research experience. This evolution will challenge us to innovate, rethink traditional approaches, and continuously respond to a changing educational landscape,” says Sharon Paynter, ECU’s chief innovation and engagement officer.

Problem-solving with AI

Chip Popoviciu installs a gateway device on top of the smokestack at Lake Mattamuskeet to support the deployment of battery-powered sensors.

ECU researchers are harnessing AI to address real-world challenges for community and industry partners.

Chip Popoviciu, assistant professor in the Department of Technology Systems, learned of a need for researchers to collect more real-time environmental data.

Connecting with other faculty and students in the College of Engineering and Technology, the team created an inexpensive sensor. Conversational Retrieval-Augmented Generation is an AI assistant that monitors certain environmental levels such as water levels, oxygen levels and air quality and reports real-time data.

CRAG communicates through text messages. Users can text 252-336-9884 to receive a response about air quality or water levels.

Though researchers intended the technology to be used on campus and in Greenville, they realized the need to expand. They built the Piton platform open network and spread devices across eastern North Carolina.

“Think of the sensors as a hotspot, like Apple has for your own personal Wi-Fi, but it can go up to 14 miles in terms of range coverage,” Popoviciu says.

Gateway devices are shown on a windmill at a farm in Carteret County.

Local farmers have benefited. Popoviciu says he was surprised at how many problems farmers face that could easily be solved with relatively inexpensive technology — less than $100 per sensor.

“Take a farmer in Hyde County. He has to take time out of his day to go out to his irrigation canal, check the water level, turn on the pump, go on with his day, then come back out to the canal at some point to turn the water off. Extremely inefficient. He now has a dashboard on his phone, which displays information from the sensors that tell him when it’s time to turn the water on and off.”

If users see data trends that indicate a problem, experts at ECU stand ready to help.

Popoviciu says his team is working to develop sensor kits and believes the technology will create new jobs for skilled workers to maintain the kits.

“I believe this has a tremendous transformative power for North Carolina. I see this as long-term infrastructure,” he says. Other AI-focused research projects at ECU include Nathan Hudson in physics, using the technology to process images and extract blood clot structures; Cameron Schmidt with biology, working on sperm analysis to diagnose infertility and potentially provide treatment; Alex Vadati in engineering, working to commercialize an AI technology that can predict pregnancy complications; and Kamran Sartipi in computer science, working on care monitoring using sensors to remotely determine the well-being of seniors living alone.

An AI ‘revelation’

Around campus and especially in classrooms, the chief concerns about AI are linked to writing assignments.

“I tell students if they are not certain about a particular use, that they should definitely consult with me first,” says Barbara Bullington, senior teaching instructor in the School of Communication. “Certainly, using AI to cheat on something, like writing a paper, is an issue for all of us. I know I’ve heard other faculty mention that they’ve had instances where students have used AI to write some or all of their paper. I think that’s probably most problematic in the writing area.

“It’s something that in faculty meetings or with emails, the big issue is to make sure we have policies on our syllabi to give students guidance. The ethical side of it is an issue. I really haven’t heard a consensus yet. … But I think most people and faculty in the School of Communication would say to take advantage of it if it’s a good resource.”

Brandon Stilley, a reference librarian in Joyner Library, used to resist AI. His views changed when he unexpectedly realized its benefits.

“I had a revelation when I was asked a question on a research topic that I did not understand at all,” he says. “Instead of gathering information from various sources, which would have taken some time, I asked ChatGPT to explain the concepts both individually and as a unified whole. It did a wonderful job of explaining something very complex in a very simple and understandable way. After that, I also discovered that the image generation GPT, DALL-E, had advanced significantly, resolving issues like distorted faces.”

Stilley was instrumental in image generation for the library’s August launch of a digital research guide to AI for students. Bright images fill the guide, which Stilley says is intuitive and a relatively easy process of feeding an idea to an image-generator program and reviewing the image it produces.

“What amazes me most about AI is its versatility,” Stilley says. “It is an equalizer in many ways. While it by no means replaces the talent and effort of traditional artists, it does allow someone like me, who is limited to drawing stick figures with a pen and paper, to communicate through images and display creativity in ways I never could before. It’s also been useful in brainstorming new active-learning activities for the classroom. Additionally, I rely on AI to analyze concepts and generate efficient keywords, a crucial step in the research process.”

In the College of Education, students use AI to spark lesson plan ideas — a practical application. After AI gives teacher candidates lesson plan options that might be effective for their setting, students then analyze the results via their contextual awareness and creativity.

Artful Aide

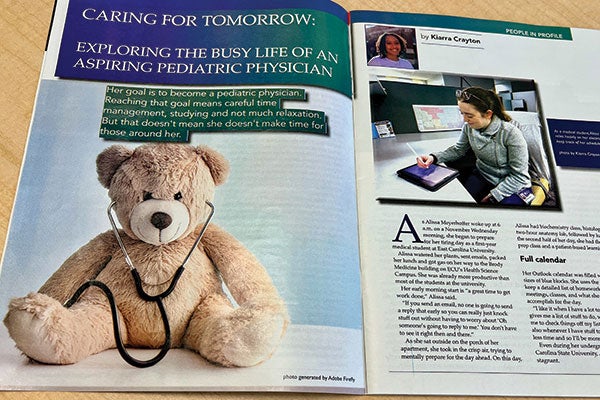

Spring 2024 marked the first time an AI-generated image appeared in Countenance magazine, which has been produced by ECU students since 2017 and is printed by The Daily Reflector.

Spring 2024 marked the first time an AI-generated image appeared in Countenance magazine, which has been produced by ECU students since 2017 and is printed by The Daily Reflector.

The right side of the opening two pages of a feature story about aspiring pediatric physician Alissa Meyerhoffer included a photo of article author Kiarra Crayton and a separate photo of Meyerhoffer writing on a tablet.

On the left was a teddy bear with a stethoscope dangling from its neck – an image generated by the AI program Adobe Firefly.

“AI is a great place for generating content, and it has opened up a lot of creative possibilities. I think we are just at the beginning of that,” says Barbara Bullington, senior teaching instructor in the School of Communication and an adviser for the magazine’s layout.

“The information AI generates can often be derivative, predictable or lacking in depth — similar to how Wikipedia provides widely accepted but not particularly inspiring perspectives,” says Todd Finley, coordinator of the English education program. “Because of the limitations of tools like ChatGPT, teacher candidates shouldn’t just outsource instructional decisions to AI. Teachers have more nuanced, cultural and emotional knowledge, which is critical for lesson planning because kids are made of feelings. Therefore, methods courses are emphasizing a type of critical thinking called curation, where candidates rapidly evaluate, select and organize curriculum.”

What’s next?

Concerns about AI range from the possibility of eliminating the need for human workers to the Hollywood generated idea of a future when AI becomes self-aware and machines dominate the world.

Nic Herndon, a professor in the Department of Computer Science, sees AI as a tool for advancement. “When it comes to ‘should we fear AI or not,’ I think we should ask ourselves, ‘How can we design AI systems that complement us and help us do things better?’” Herndon says.

David Hart, an assistant professor of computer science, says human adaptation will be important.

“AI is an incredibly powerful digital tool, but it is only as good as the human who directs it,” Hart says. “Just like the internet and the smartphone, AI will change the world in a way that will require each person to rethink how they have done things before. Our future will depend on the ability of individuals and societies to adapt. A lot of people think the danger of AI is that if it gets too smart, it will revolt like we see in the movies. We are far away from that possibility, in my opinion. In reality, AIs are very good at optimizing the goals that we give them, so the true danger is what humans train AI on and how we use it. AI will reflect our desires and our biases.” Adapting seems inevitable to many experts.

“We owe it to our students to help them navigate this world and understand what these tools can do,” says Zach Loch, ECU’s chief information officer. “And how to best use these tools when they get to the real world, because the truth is they’re going to be using them.”

As Milks moves closer to that real-life scenario of graduation and professional aspirations, she downplays the idea that AI might replace human production.

“Personally, I’m not worried about that,” she says. “AI is only possible because of preexisting work from humans. I think AI can be used as a collaborative tool for designers and artists. Human minds and ideas, in my opinion, are far more impressive than artificial intelligence. AI is not a threat. It’s just another asset we could use to create.”