Wings of the Purple and Gold

East Carolina University has sent nearly 200,000 alumni out into the world – and more than a few into the skies above. Over the next few pages, they take you with them to war zones and exotic locales, on lifesaving missions and into the sky in solitary silence as they talk about their experiences in the air, what led them there, the challenges they’ve conquered and the impact ECU has had on their careers.

In 2014, somewhere in Afghanistan, Marine Corps pilot Jacquelyne Nichols ’05 set down her Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallion in a dust cloud to pick up troops. Taliban fighters opened fire.

Nichols poses in front of a CH-53E Super Stallion like the ones she flew in Afghanistan.

Because of the front stops on the mounted machine gun, her crew chief couldn’t get the right angle to return fire. “He opened the side door, stepped out, took a knee and started returning fire with his personal rifle,” she says. “He placed himself in harm’s way to lay suppressive fire so these Marines could board our helicopter. It was very dynamic; it was very kinetic for us.”

And it must have seemed a long way from the fourth-grade project on Amelia Earhart that cemented her aspirations to become a pilot.

But it wasn’t a straight shot from a girl with a dream to pilot in a combat zone. At Havelock High School, Nichols was a hurdler with aspirations of being on the track team in college, but a car crash her senior year and the resulting injuries slowed her a step. At ECU, she majored in exercise and sport science, played club rugby and worked at the rec center. After graduation, she took a job as a health and wellness director in Suffolk, Virginia. She took flying lessons and wanted to join the military – her dad had been a machine gunner in Vietnam then a recruiter for the Marines – but she thought her bad vision would keep her out of the cockpit. Her flight instructor told her the military had started accepting people with vision corrected by laser surgery.

She got the surgery, then visited a recruiter and soon was in the Marines. In Officer Candidate School, she was charged with leading physical fitness training for her company a handful of times – a responsibility rarely given to a candidate. She drew on her years at ECU.

“My professors talked about professionalism, drive, excellence,” she says. “Those lessons carried over a lot to me joining the Marine Corps and getting into aviation. Attention to detail is so important in aviation. It can be the difference between life and death.”

Jacquelyne Nichols poses for a photo with her friend, Lily, whom she met at Charlotte-Douglas Internal Airport. “Lily and her parents were headed to Disney World for Lily’s birthday,” Nichols says. “Her dad was holding her and waving at me from inside the airport in Charlotte as we were parking the aircraft at the gate. Once we were safely parked, I opened my window from the flight deck and leaned out and gave her a big wave back, which thrilled her! When I got off the plane, I sought her out. She acted a bit shy at first, but eventually opened up. Her parents told me that I was a bit of a celebrity to Lily because I was the first pilot she ever met. It meant a lot to me to be able to have an impression on this little girl. Being a positive role model for girls and young ladies is important to me.”

Nichols’ goal was to fly a helicopter. “When I think of the Marine Corps, I think of the ground troops,” she says. “That’s our main effort. I wanted that interaction with them, picking them up, dropping them off, supporting them however we could.”

She competed for and won the single aviation contract that was available to her company of more than 200 Marines and completed CH-53E training in 2013 at Marine Corps Air Station New River near Jacksonville. Then it was off to San Diego for her first squadron tour. In January 2014, she deployed for six months to Afghanistan.

“I didn’t join the Marine Corps to sit on the bench,” she says. “That’s what I wanted. I’m part of the 9/11 generation, so I joined the Marine Corps wanting to get into the fight.”

“We had a mission where we took rounds to our helicopter. And one of the bullets actually stopped in my seat underneath me. I felt it; I felt the vibration, the ping when it hit.”

As her career progressed, she was ready for something other than a cantankerous chopper that first entered service in 1981. She had gotten married, and her husband was also in the Marine Corps.

“I wanted to keep flying and wanted to be stationed with him,” she says. “I just wanted to fly something safer, so I requested the Cessna Citation Encore (the UC-35, an executive jet). They tried to push me into picking my husband or flying, and I refused, and it all worked out. I got really lucky.” She flew the Encore for five years – three on active duty and two in the reserves, where she’s now a major.

Nichols, her husband, R.B., and Pirate enjoy donning buccaneer gear and celebrating pirate life.

In 2022, Nichols joined American Airlines as a first officer on the Airbus. It was a challenging hiring process, and a friend and former female Marine coached her through it.

“Only 4% of major airline pilots are women, so I’m a minority in this industry, and I have been my entire career,” she says. “And I faced a lot of adversity in the Marine Corps, and it’s exhausting.” American, she says, prioritizes opportunities and equity. Her long-term goal with the company is to pilot the Boeing 787 Dreamliner and to continue to open doors for women aviators.

Nichols, 41, has a master’s degree in public leadership from the University of San Francisco. Her thesis dealt with infertility among service members, especially aviators, and she advocates for policy change. In May, she was featured on NBC News regarding her infertility experiences in the military and her advocacy work. She and her husband are pursuing in vitro fertilization in hopes of starting a family to raise on their 25-acre ranch in New Mexico. One of their dogs is named Pirate, and they fly a Jolly Roger out front.

“It’s a lifestyle, and we really enjoy it,” she says.

– Doug Boyd

When a plane operated by Jet Logistics reaches its destination, it brings more than just cargo. It brings life.

The company, founded by W. Ashley Smith Jr. in 2002, is one of the biggest and busiest organ flyers in the country. Smith’s experience flying organs began as a co-pilot on a flight in 1986.

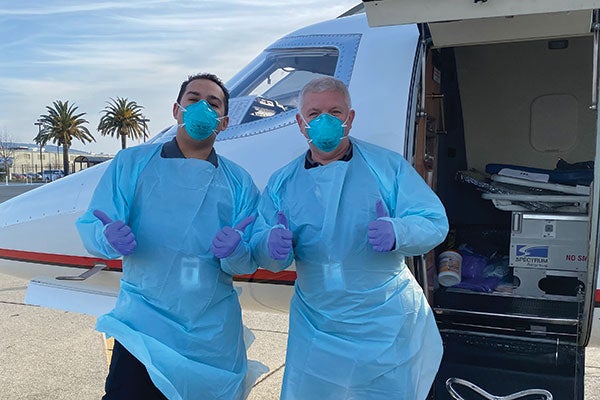

Co-pilot Stephen Stoller, left, and Ashley Smith ’91 prepare to load the first COVID-19 patient in the U.S. in February 2020.

When flying organs, every minute from takeoff to touchdown is critical.

“An organ procurement organization reaches out and tells us they have a team and organ that need to be transported,” says Smith ’91. “Once an organ is removed from a body, the organ is raced to the airport. We’re on the ground waiting for the organ and then fly to where the recipient is located as quickly as possible. Each organ has a certain amount of time it can be out of the body, and we know before each flight what the organ is and how long we have to get it there.”

In 2023, Jet Logistics transported 294 patients and more than 1,500 organs. The company accomplished this while flying 5,100 hours over four continents.

“If you don’t do this because you love helping others, you’re in the wrong industry,” says Smith. “I love helping others, and I love playing with airplanes, and I’m able to bring them together every day.”

Smith’s passion for flying developed early.

“I grew up on a farm between Kinston and Greenville,” he says.

“The farm where I grew up was in the flight path for aircraft from Seymour Johnson Air Force Base. I saw the planes overhead and knew that’s what I wanted to do with my life.”

A patient is about to be loaded.

Smith transferred to ECU from Lenoir Community College. He majored in industrial technology before pursuing a career in the U.S. Air Force. Smith says that due to government budget cuts, that military career never materialized.

“Truthfully, my main reason for attending ECU was that I wanted to be a pilot in the military. To be a pilot, you had to be an officer, and you needed a degree to become an officer,” he says.

Looking to make an impact at ECU, he endowed the W. Ashley Smith Jr. Transfer Scholarship in the College of Engineering and Technology, which annually supports students majoring in the Bachelor of Science in industrial technology transfer program.

“I feel like each generation should do what it can to help make things better for those that follow,” says Smith. “It’s something to help those following in my footsteps; a way to pay it forward.”

– Steven Grandy

An opportunity to see the world seemed a perfect fit for Amy Fenton ’14 when flight attendant popped up as a career option for someone with a history degree.

Amy Fenton ’14

As a flight attendant for Alaska Airlines since 2015, Fenton has embraced the opportunities that have come from traveling three-and-a-half million miles.

“I’ve stayed in a castle in Germany, explored Alaska and Hawaii and had so many opportunities to see the world as a benefit of being in the airline industry,” Fenton says. “There are so many surreal moments that come with flying. You get to see these incredible things.”

Fenton said flying to Alaska is still her favorite route. “The views just don’t get old,” she says. “You don’t get over that kind of majesty.”

Among her favorite experiences are a “roots” trip to Ireland, where she learned about her mother’s family history, and taking her parents to Hawaii in 2019.

While the ability to fly is a significant perk for airline employees, it doesn’t come without obstacles like the one Fenton faced when she and her parents tried to fly back to North Carolina. The only route with seats meant an additional 24 hours and a flight to San Francisco. But it worked out.

“I met my partner on that flight (because) he was working it. I’m so grateful that we couldn’t get on another flight,” Fenton says. The couple flies together frequently now, most often working Alaska Air trips to Hawaii.

A flight attendant schedule averages 15 days a month. Fenton describes the job as a bit chaotic and hard on the body because of time zone changes and constantly going somewhere different.

From climbing peaks, such as the Bird Ridge in Alaska, to running marathons and international travel, Amy Fenton’14 takes on the adventures that come her way in her career.

“It’s exciting and interesting, always,” Fenton says. “It’s really what you make of it. You can get to any city and sit in your hotel the whole time or get out and explore.”

Flight attendants receive six weeks of training to prepare for the role and two days of recurrent training annually. They are prepared for fire, water and land evacuations, medical issues and arctic survival. Disruptive passengers have become prevalent, and training on de-escalation has increased in response.

On the plane, her job consists of checking security equipment, flight briefings for passengers with special needs, making sure supplies are adequate and helping passengers have the best journey possible.

One recent flight has stayed in Fenton’s memory. A passenger on a Seattle to Newark flight shared that he was on his way to see his mother, who was dying.

“When we landed, we asked everybody to just stay seated so this guy could get off the plane and get to his mom as quickly as possible. Everybody was so respectful,” Fenton says. “We got an email from his wife a couple of days later saying that he made it. He was able to say goodbye to his mom.”

– Patricia Earnhardt Tyndall

Lawrence Ward ’02 works to keep people safe on the ground and in the air.

Lawrence Ward ’02 poses on an AH-64 Apache at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Ward is an Apache helicopter pilot and serves as squadron safety officer at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he also mentors and trains new pilots. Fort Campbell is home of the 101st Airborne Division, the only air assault division of the U.S. Army.

“ECU gave me a great foundation,” Ward says. “From late night studying, working on projects, there was great support to help me succeed.”

Ward grew up in Chesapeake, Virginia, where his father, Lawrence, was a shipbuilder and his mother, Jeannette, drove a bus. Ward earned a scholarship and ran track at ECU, where he was a multiple All-America title winner competing in the 200-meter, 400-meter and the 4×400 relay events. As a senior, Ward’s 4×400 relay team set an ECU record of 3:02.81 at the NCAA championships.

“I chose ECU because it felt like home. The team, campus, city – I felt welcome. It was a great environment,” Ward says.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in electronics in 2002, when the internet was cranking up. He thought he would be working with network databases or running cables. He said the military wasn’t on his radar when he graduated, but after applying for hundreds of jobs without success, he needed to make some decisions. He and his wife had a son on the way, and his brother, Kevin, who was already in the military, suggested he consider joining.

Once enlisted, Ward worked in electronics, which fit perfectly with his major and abilities. He was still working in electronics and on aircraft when he was deployed to Afghanistan in the early days of the war. Another yearlong deployment came after that. One day he was talking with a senior maintenance test pilot, who asked if he had ever thought about flying helicopters.

Encouraged by his wife, Jennifer, Ward passed the entrance test and was selected through a competitive process to train as an Army aviator. “It is challenging,” he says.

In his 20 years in the military, he’s been stationed at five bases and deployed five times to Afghanistan and Iraq.

“I love being in the sky supporting the people on the ground. I’m up there for a reason – to help get the people on the ground back home,” Ward says. “We all join to serve, and I want to help do my part to get somebody back home.”

Last year, he was promoted to chief warrant officer 4 at Fort Campbell. As the squadron safety officer, Ward ensures adherence to aviation safety regulations and standards, conducts accident investigations and advises the commander on safety and risk management. Ward is also passionate about mentoring and training junior pilots, who benefit from his experience and expertise.

He intends to retire from the military next year and hopes to transition into the safety field in the public or private sector. He’s looking forward to spending more time with his family. His wife is a real estate agent and special education teacher. They have three sons. Lawrence Jr., or L.T., is a rising junior at ECU, where he is majoring in criminal justice with interest in working in law enforcement. Cameron is a sophomore at Middle Tennessee State, where he is studying aerospace and wants to be an airline pilot. He got his pilot’s license at age 17. The youngest, Sean, will be heading to high school and is interested in cybersecurity, networking and programming.

– Crystal Baity

Andy Torrington ’93 has experienced the thrill of jumping off a cliff and flying away as a longtime hang-gliding instructor in Nags Head.

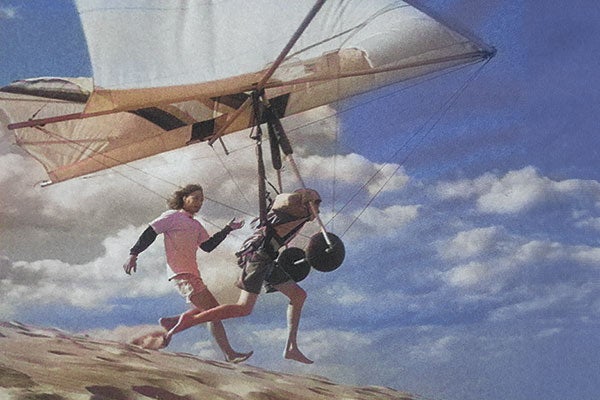

A student takes off during Torrington’s days as a hang-gliding instructor at Jockey’s Ridge in Nags Head.

Torrington has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and works as a staff tax professional with a Virginia-based accounting and consulting firm.

“I decided to major in business because it seemed like the broadest category for me at the time,” he says. “I really did not know what I wanted to do professionally. I have always been a math nerd and a technical analysis geek. I have been doing my own taxes since I started working as a lifeguard when I was a teenager, and because I knew the 1040 form, my friends would always seek me out and ask me to help them file. I didn’t pursue accounting, however. I was too starstruck with hang-gliding.”

He started hang-gliding in 1990 while a student at ECU. “It was not easy for me to focus on business school, but applying everything I learned to the newly formed hang-gliding industry got me through it,” he says.

Torrington says he was drawn to ECU because he always loved North Carolina, and it had the best swim team on the East Coast when he was recruited to swim out of his New Jersey high school. ECU won the 1989 Colonial Athletic Association title his freshman year.

As a sophomore, he stopped swimming to focus on school and work. He applied to student recreation as a lifeguard, but they didn’t need any at the time and instead hired him as an outdoor recreation supervisor for the newly established adventure program. He took many rock-climbing trips to western North Carolina and Virginia and fell in love with the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Appalachian Trail.

Looking for summer work, he attended a job fair at Minges Coliseum, hoping to lifeguard on the Outer Banks. But the lifeguarding interviewer never showed up. While he was waiting, he started talking to two men at a nearby booth who were looking for instructors for their hang-gliding school in Nags Head.

Andy Torrington ’93

“They told me that for $25, I could sign up for a lesson, and if they ended up hiring me, I could get a refund,” Torrington says. “Cash came out of my pocket in an instant. Two days later I took my first flight, and it was really, really perfect. I had found my way. It felt like I had finally found my way home.”

He eventually moved to the West Coast, where he worked for several different hang-gliding schools and built gliders in a factory in Salinas, California. But he missed the Outer Banks.

“There are no dolphins in California, and the beaches are not clean, and the water is cold,” he says. “I missed the warm East Coast surf, so I came back to North Carolina in the late 1990s and became the assistant manager of Kitty Hawk Kites’ outdoor recreation program.”

Torrington started the company’s kiteboarding school in 2000. He also worked for the Professional Air Sports Association, helping to develop guidelines that kiteboarding and hang-gliding schools use to qualify for commercial liability insurance.

In addition, Torrington was picked to pilot a replica of the Wright brothers’ glider built by the Wright Experience. They recreated the brothers’ early test flights to coincide with the 100th anniversary celebration on the Outer Banks in 2003.

“After an amazing day on the dunes, we hatched the idea of opening the experience up to the public,” Torrington said. “With two instructors running the wing with tethers, we could safely duplicate the experience, and it became a huge success.”

The 1902 Wright Glider Experience at Kitty Hawk Kites gives participants another way to fly. “People love it,” he says.

After Torrington and his wife, Laura, had their two sons, he decided to stop teaching hang gliding and works for an accounting firm full time. The family and their 15-year-old pit bull, Tornado, live just a couple of miles north of the sand dune where Torrington learned to fly.

– Crystal Baity