Glass Class is in Session

The golden hour arrives in Farmville, where the sun slowly slips beneath acres of tobacco and cotton fields surrounding this eastern North Carolina town, revealing hues of blue, orange, yellow, pink and, of course, purple.

The drive is less than 30 minutes from East Carolina University’s campus in Greenville, and students make the trip four evenings a week, catching a glimpse of nature’s majesty on their way to class at the GlasStation.

ECU opened the studio five years ago in collaboration with the town. Each semester, undergraduate and graduate students sign up for glass blowing at ECU, the only university that offers it in the University of North Carolina System.

Charity Ray, who is majoring in art with a concentration in graphic design, needed another class to finish the art studio requirements for her major. “Out of all the classes I could’ve taken, glass blowing was something that I wanted to know more about,” she says. “I automatically assumed it was going to be hard because of how clumsy I was, but no matter how many times I messed up, I wasn’t afraid to try again.”

Glass blowing has a steep learning curve, a choreographed process of heat, movement and pressure, which becomes intuitive with practice, says Michael Tracy, teaching assistant professor in the School of Art and Design.

“Surprisingly, after being in the class for a little bit over a month, I have gotten the basics of controlling the glass and not being afraid of getting close to the heat,” says Ray of Severn, Maryland. “I did not know how every detail that goes into making a glass piece is up to the artist. In the end, if you break it, just shake it off and start again.”

ECU students Bansari Patel, left, and Charity Ray work

together on Ray’s cup.

“We hope that the GlasStation provides those that visit an opportunity to experience all of what art can do for us as individuals and as a community.”

Nick Bisbee, a first-year graduate student in ceramics, has enjoyed creating designs for molds for his hand-blown glass. He caught the “glass bug” in his first class and now is a teaching assistant with Tracy. Bisbee hopes to eventually teach ceramics at a university.

“My favorite thing about glass is definitely the aesthetics of it, the fact that you can make something that refracts light in a way that no other material really can and the way that light can move through it in ways that it doesn’t really with other materials,” he says.

Bisbee’s other medium is clay, “which weirdly translates extremely well into glass. Instead of throwing on a wheel, you’re throwing fully sideways, and you can’t touch it with anything other than tools, even though you really want to.”

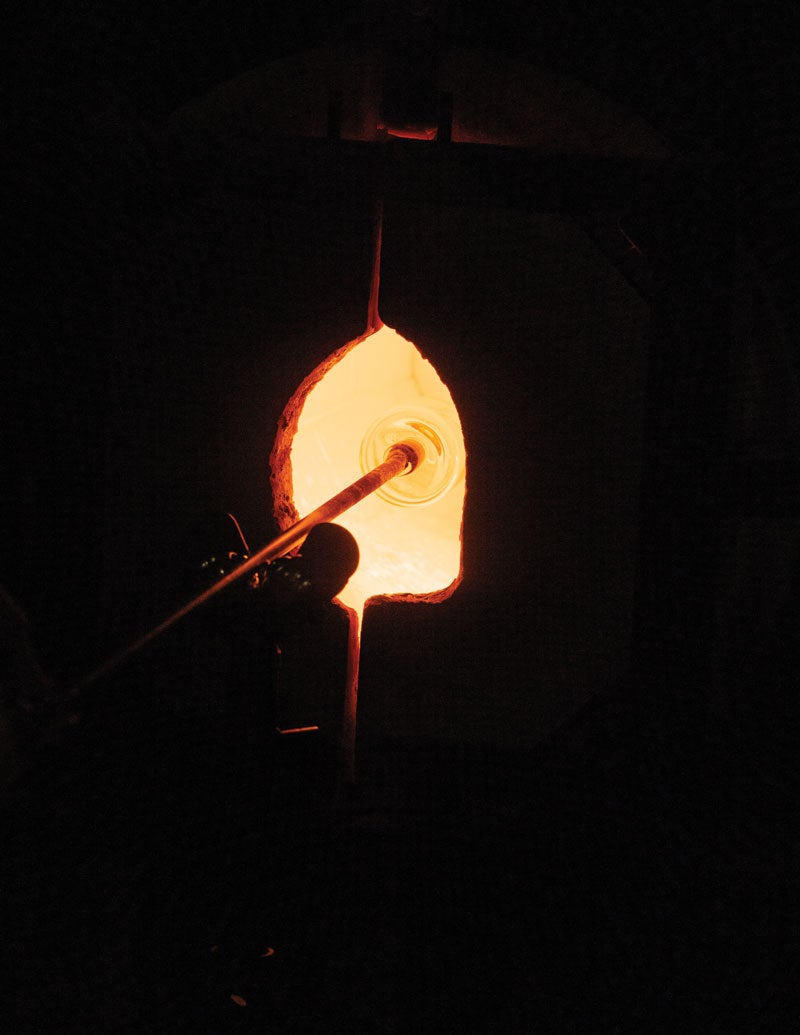

Students are shaping glass at temperatures between 1,600 and 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit, although it’s closer to 2,100 degrees when first pulled from the furnace. The material can crack if it drops below 1,000 degrees and isn’t cooled slowly.

Todd Edwards is a Farmville Group member who helped bring ECU’s glass classes to town.

ECU student Christopher Uteck uses a grinding wheel in the cold room.

The GlasStation is helping fulfill a vision to use the arts to revitalize downtown Farmville. Almost a decade ago, members of the Farmville Group, a volunteer economic development association, and the Tabitha M. DeVisconti Trust, which owns the building, approached ECU about the possibility of opening a studio or art space in Farmville.

At that time, more than half the town’s storefronts were empty or abandoned. In response, ECU proposed a glass art facility that would not only serve as a classroom for students but would become a destination for anyone interested in glass blowing.

“It’s a vital place now,” says Todd Edwards, a local builder, developer and Farmville Group member involved in the effort. “Just the energy that the GlasStation brings, that big risk that ECU took, and that Michael took to come here. The attention it draws, it’s amazing when they have demonstrations. Often it’s standing room only.”

The GlasStation’s name is a nod to the building’s former life as a Gulf service station.

Glass is turned at temperatures between 1,600 and 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit in the furnace.

ECU’s presence has rejuvenated interest from residents and beyond. “Mike’s done a great job of promoting glass art,” Edwards says. “It’s really performance art meets art world because there’s a physical, tangible product in the end. To watch glass being made is absolutely fascinating.”

Finished glass pieces are lined up on a shelf.

Michael Tracy, teaching assistant professor in the ECU School of Art and Design, has been the glass art instructor in Farmville since the facility opened.

‘Creative roots’

Glass blowing involves heating a glass tube, called a blowpipe, and manipulating it to shape the molten glass as it cools. ECU’s glass blowing classes are capped at eight students, a purposely small group to accommodate available workspace and equipment. Over the past five years, Tracy has taught about 150 ECU students the art of glass blowing.

The medium has not changed much, Tracy says, since humans began making glassware.

“I love the fact that I feel like I have a connection with the Mediterranean and Roman glass blowers 2,000 years ago. That kind of feels a little special,” he says. “New technologies are great, but I also feel a lot of them are transient, whereas with glass blowing, the only change has been our fuel source. It probably won’t change drastically any time soon.”

The forms were all influenced by pottery and translated to glass, Tracy says. “Form follows function, so if you’re trying to make a vase, only certain shapes are going to work really well for a vase,” he says.

Graduate student Nick Bisbee fires a mold in one of the GlasStation’s furnaces.

In 2019, ECU’s College of Fine Arts and Communication received a $20,000 National Endowment for the Arts grant to research the cultural and economic impact of the glass blowing studio in Farmville. ECU was one of 19 organizations in North Carolina to receive the competitive funding.

ECU and the college’s role in regional transformation — part of the university’s core mission — comes to life here in the form of the orange glow of hot glass on its way to becoming a piece of art.

“We know that the arts have the ability to transform us in many ways,” says Linda Kean, dean of the College of Fine Arts and Communication. “In the case of the GlasStation, giving people the opportunity to participate in the creation of a piece of work that is uniquely their own can be powerful.

“We hope that the GlasStation provides those that visit an opportunity to experience all of what art can do for us as individuals and as a community. We continue to look to the future to find ways to collaborate with Farmville and other communities to come together to create art in its various forms.”

The GlasStation’s impact continues to unfold today. “And it just keeps going. We have lots of tenacles to what’s going on and the creative roots that this place has put into town,” Edwards says.

“The ECU connections run deep, and we’ve had a lot of ECU alumni come through here. It’s brought people to town in many, many ways,” he says. “Everyone is proud of ECU, and we’re so proud to have an ECU satellite to the campus here in town. For us, it’s a really big deal.”