Listen to the flame

A return to Estonia this year gave potter Anne Pärtna ’07 time to explore and try new materials she hopes will soon lead to an art show.

Anne Pärtna

Pärtna had a monthlong international residency — her first — at ARS Ceramics Center in the northeastern European country that juts into the Baltic Sea, where she grew up on a small family farm.

Because of the timeframe and COVID-19 restrictions, she wasn’t able to teach, but she worked with other artists at the center. She also gave an online lecture to students at her alma mater, the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA), and to Estonian Ceramists Union members about life in Seagrove, where she and her husband own and operate Blue Hen Pottery.

“It’s good for an artist to occasionally work in a completely different setting,” Pärtna said. “It can take you in new directions, open you up to new possibilities.”

Pärtna first came to ECU for a semester in 1998 through an exchange program as an undergraduate ceramics student at EKA.

At the time, ECU art professors took groups of students to the Baltic States, Finland and St. Petersburg, Russia, for an immersive cultural exchange and art experience. Pärtna met an ECU professor, who encouraged her to come to ECU. “It was not easy to do all the paperwork, get the proper documents in order and raise the money, but somehow I managed,” she said.

In 2004, Pärtna was accepted to ECU’s ceramics graduate program, where she also met her husband, Adam Landman. After graduation, both were offered internships at the newly opened STARworks arts organization and gallery in the town of Star, where Landman is project manager. Pärtna and Landman settled nearby in Seagrove, known for generations of pot makers. Their studio is named for the road where their family and career began. They’ve also kept chickens for more than 10 years.

“ECU feels like home to me. I can say that I grew up there in a way. And my children spent their early years attending wood firings and iron pours at ECU, so we all have fond memories and feel like our teachers and peers were our extended family,” Pärtna said.

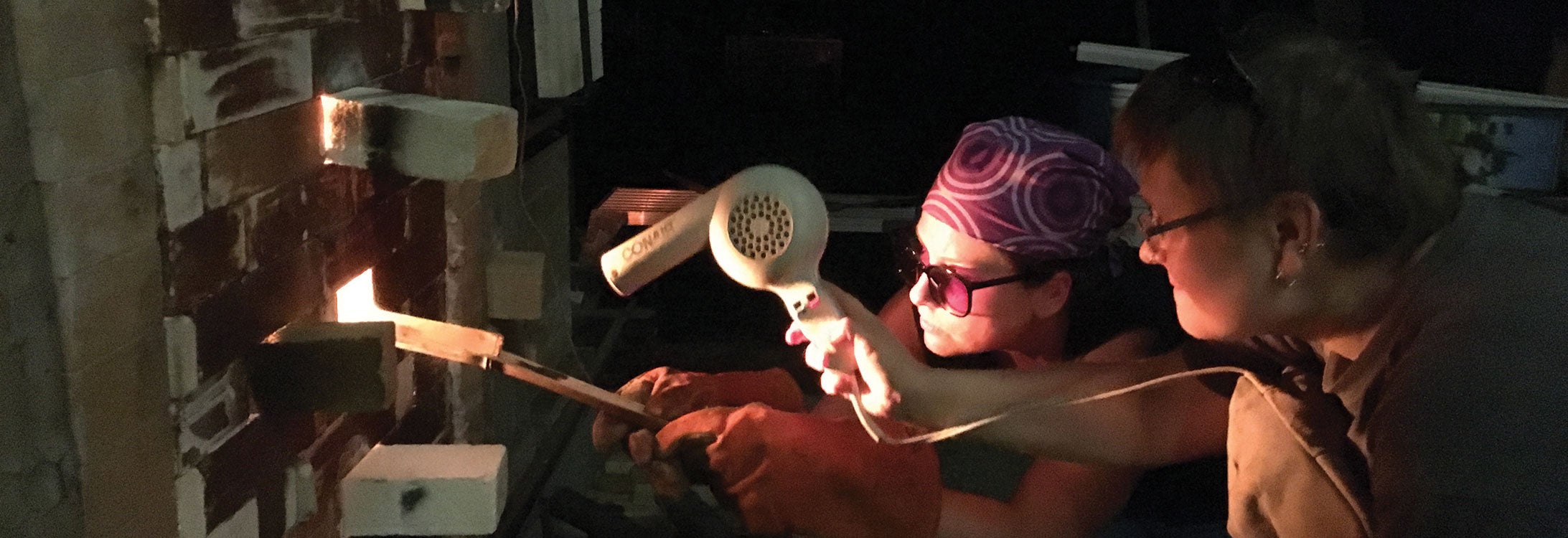

Beyond the wheel, her favorite part of making pottery is the firing of the stoneware, although it requires a lot of work — cutting, splitting and stacking the wood, preparing and loading the kiln, and the continuous stoking of wood that can take several days, she said.

“I have to slow down and pay full attention, be in tune with the kiln and the environment, listen to the flame,” Pärtna said. “Pottery in general keeps you humbled, and the wood-firing process especially so. Sometimes you have mediocre or even bad results, sometimes a shelf breaks and you lose a lot of work. But when it’s good, it can be amazing — the path of flame recorded on the surfaces, each piece unique, never to be repeated again exactly the same way.”